A self-powered microneedle patch has been created by researchers to track a variety of health parameters without the need for external devices or blood draws. The researchers showed that the patches could gather biomarker samples for anywhere from 15 minutes to 24 hours in proof-of-concept testing using synthetic skin.

"Biomarkers are measurable indicators of biological processes, which can help us monitor health and diagnose medical conditions," says Michael Daniele, corresponding author of a paper on the work. "The vast majority of conventional biomarker testing relies on taking blood samples. In addition to being unpleasant for most people, blood samples also pose challenges for health professionals and technology developers. That's because blood is a complex system, and you need to remove the platelets, red blood cells, and so on before you can test the relevant fluid.

Related Wearable Sticker Can Identify Real Human Emotions

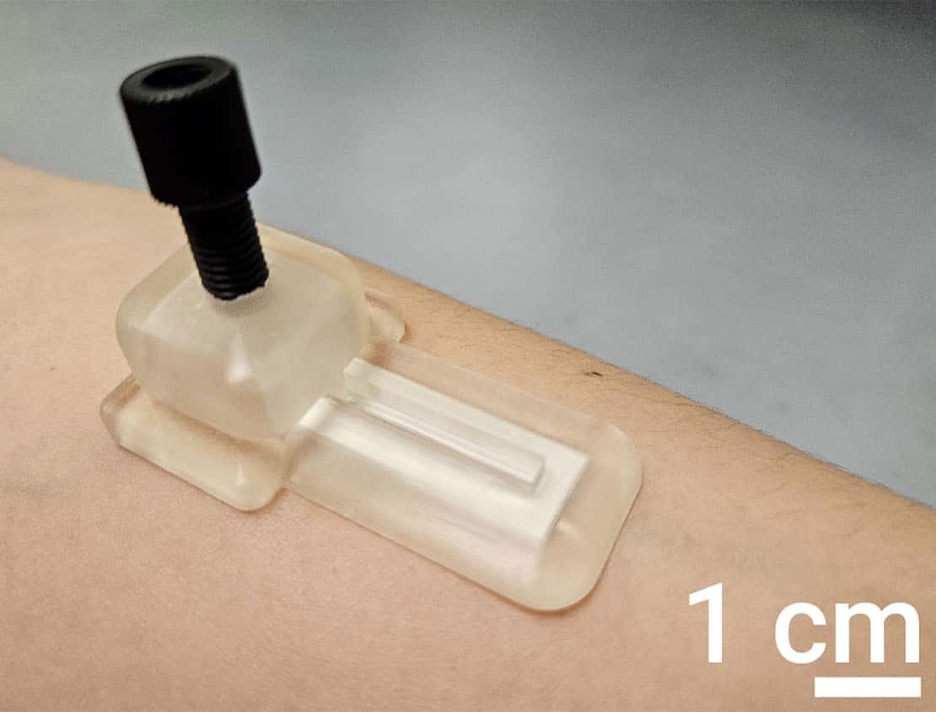

The wearable device is made up of a polymer housing that contains three stacked layers of material: a layer of polyacrylamide hydrogel loaded with glycerol on top, an absorbent paper strip in the center, and a collection of small, sharp-stud-like microneedles on the bottom. The needles only painlessly puncture the epidermis when the patch is pushed against the skin and adheres to it; they do not penetrate to the nerve endings beneath.

The microneedles, which are composed of methacrylated hyaluronic acid, swell up and begin wicking the interstitial fluid (ISF) into the paper as they come into contact with it. The fluid's biomarker concentrations match those in the blood, reports Ben Coxworth in New Atlas.

Osmotic pressure is the result of the glycerol imbalance between the hydrogel layer and the ISF as it travels through the paper's microfluidic channels and makes contact with it. Until the paper is soaked, the pressure pulls more ISF up from the skin.

The last step involves removing the patch from the skin, removing the paper strip from the patch, and swiftly and simply analyzing the interstitial fluid in the paper. "ISF makes for a 'cleaner' sample – it doesn’t need to be processed the way blood does before you can test it," says Prof. Daniele, who is affiliated with both universities. "Essentially, it streamlines the biomarker testing process."

According to laboratory experiments conducted on models of synthetic skin, the patch was able to draw and store ISF for up to 24 hours and collect quantifiable amounts of the fluid in 15 minutes. In addition to creating an electronic patch-paper-processing apparatus that accomplishes the task automatically, the scientists were able to measure the cortisol levels in the ISF with accuracy. There are currently plans to develop more tools for measuring various biomarkers.

"The highest cost of the patches would be manufacturing the microneedles, but we think the price would be competitive with the costs associated with blood testing," say Daniele. "Drawing blood requires vials, needles and – usually – a phlebotomist. The patch doesn’t require any of those things."

Human testing of the technology is now underway.