A step toward human-machine interfaces that function in the chaotic conditions of daily life, engineers at UC San Diego have developed a soft, AI-powered wristband that can interpret your arm motions even during intense activity and utilize them to control machines in real time.

Wearable technologies with gesture sensors work fine when a user is sitting still, but the signals start to fall apart under excessive motion noise, explained study co-first author Xiangjun Chen, a postdoctoral researcher in the Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. This limits their practicality in daily life. “Our system overcomes this limitation,” Chen said. “By integrating AI to clean noisy sensor data in real time, the technology enables everyday gestures to reliably control machines even in highly dynamic environments.”

For example, the technology could allow people with restricted mobility or patients undergoing rehabilitation to use robotic devices using natural gestures instead of using fine motor skills. The technology may be used by first responders and industrial workers to operate tools and robots without using their hands in hazardous or high-motion situations. Even under turbulent conditions, it might allow remote controllers and divers to control underwater robots. The approach could improve the dependability of gesture-based controls in commonplace consumer gadgets, reports UC San Diego.

Professors Sheng Xu and Joseph Wang of the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering's Aiiso Yufeng Li Family Department of Chemical and Nano Engineering collaborated on the project.

This is the first wearable human-machine interface that functions consistently under a variety of motion disturbances, as far as the researchers are aware. It can therefore adapt to how individuals move in real life.

Related Meta’s Bracelet Can Replace Your Mouse and Keyboard

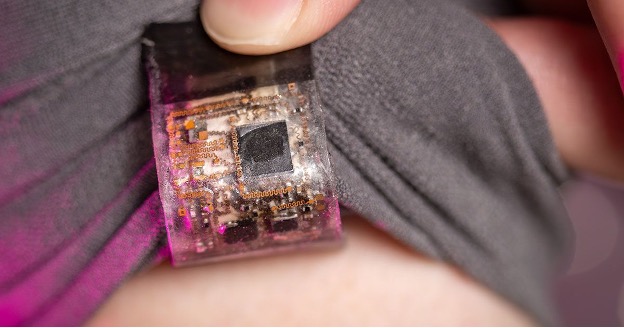

The device is a cotton wristband with a soft electrical patch adhered to it. It combines a Bluetooth microprocessor, a stretchable battery, and motion and muscle sensors into a small, multi-layered system. A composite dataset of actual motions and situations, ranging from sprinting and shaking to the motion of ocean waves, was used to train the system. A specially designed deep-learning framework receives and processes signals from the arm, eliminates interference, deciphers the gesture, and sends a real-time instruction to operate a machine, like a robotic arm.

“This advancement brings us closer to intuitive and robust human-machine interfaces that can be deployed in daily life,” Chen said.

Several dynamic circumstances were used to test the system. The device was used by the subjects to operate a robotic arm while they were running, subjected to a variety of disruptions, and exposed to high-frequency vibrations. The Scripps Ocean-Atmosphere Research Simulator at UC San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which replicated both lab-generated and actual sea motion, was used to evaluate the device under simulated ocean conditions. The system consistently provided precise, low-latency performance.

This research was initially motivated by the notion of assisting military divers in controlling underwater robotics. However, the scientists quickly discovered that motion-related interference wasn't limited to underwater settings. It is a prevalent issue in the wearable technology industry that has long restricted how well these systems function in daily life.

“This work establishes a new method for noise tolerance in wearable sensors,” Chen said. “It paves the way for next-generation wearable systems that are not only stretchable and wireless, but also capable of learning from complex environments and individual users.”